Supreme Court blocks Trump’s bid to end DACA, a win for undocumented ‘Dreamers’

Washington Post – The Supreme Court on Thursday rejected the Trump administration’s attempt to dismantle the program protecting undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children, a reprieve for nearly 650,000 recipients known as “dreamers.”

It will likely elevate the issue of immigration in the presidential campaign, although public opinion polls have shown sympathy for those who were brought here as children and have lived their lives in this country. Congress repeatedly has failed to pass comprehensive immigration reform.

President Trump responded to the decision by tweeting his displeasure and turning it into a call for his reelection, with a specific focus on gun-rights supporters: “These horrible & politically charged decisions coming out of the Supreme Court are shotgun blasts into the face of people that are proud to call themselves Republicans or Conservatives. We need more Justices or we will lose our 2nd. Amendment & everything else. Vote Trump 2020!”

The administration has tried for more than two years to “wind down” the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, announced by President Barack Obama in 2012 to protect from deportation qualified young immigrants. Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions advised the new Trump administration to end it, saying it was illegal.

But, as lower courts had found, Roberts said the administration did not follow procedures required by law, and did not properly weigh how ending the program would affect those who had come to rely on its protections against deportation, and the ability to work legally.

He added: “We address only whether the [Department of Homeland Security] complied with the procedural requirement that it provide a reasoned explanation for its action. Here the agency failed to consider the conspicuous issues of whether to retain forbearance and what if anything to do about the hardship to DACA recipients. That dual failure raises doubts about whether the agency appreciated the scope of its discretion or exercised that discretion in a reasonable manner.”

The court’s four most conservative justices dissented. Justice Clarence Thomas said the program was illegal, and that the court should have recognized that rather than extending the legal fight.

“Today’s decision must be recognized for what it is: an effort to avoid a politically controversial but legally correct decision,” Thomas wrote. “The court could have made clear that the solution respondents seek must come from the legislative branch.”

Instead, he said, the court provided a “stopgap” measure to protect DACA recipients, and “has given the green light for future political battles to be fought in this court rather than where they rightfully belong — the political branches.”

He was joined by Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Neil M. Gorsuch. Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh dissented on other grounds. He said that even if the department had not provided adequate reasons initially for ending the program, it has since supplied them, and should not have to start over.

Immigration advocates were euphoric over the court’s actions.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra (D), who led a coalition of 20 states and the District of Columbia in bringing the fight, said ending DACA “would have been cruel to the hundreds of thousands of Dreamers who call America home, and it would have been bad for our nation’s health.”

He said Congress should “permanently fix our broken immigration system and secure a pathway to citizenship.”

Obama responded on Twitter as well: “Eight years ago this week, we protected young people who were raised as part of our American family from deportation. Today, I’m happy for them, their families, and all of us. We may look different and come from everywhere, but what makes us American are our shared ideals,”

And he put in a plug for presumptive Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, his vice president. He said future reform depends on electing Biden “and a Democratic Congress that does its job, protects DREAMers, and finally creates a system that’s truly worthy of this nation of immigrants once and for all.”

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R), on the other side, said the decision “does not resolve the underlying issue that President Obama’s original executive order exceeded his constitutional authority.” He has filed a suit alleging that in federal court in Texas.

Nearly 800,000 people over the years have participated in the program, which provides a chance for enrollees to work legally in the United States as long as they follow the rules and have a clean record.

More than 90 percent of DACA recipients are employed and 45 percent are in school, according to one government study. Advocates recently told the Supreme Court that nearly 30,000 work in the health care industry, and their work was necessary to fighting the coronavirus pandemic.

While the program does not provide a direct path to citizenships, it provides a temporary status that shields them from deportation and allows them to work. The status lasts for two years and can be renewed.

The Trump administration said the DACA program, which Obama authorized through executive action, was unlawful. But even if it was not, Trump’s lawyers argued, the Department of Homeland Security has the right to terminate it.

Lower courts disagreed. They said the administration must provide other legitimate reasons for the action, because it has offered the protection to those undocumented immigrants who volunteered information about their status.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit said the administration had not complied with legal requirements in trying to end the program.

“To be clear: we do not hold that DACA could not be rescinded as an exercise of Executive Branch discretion,” Judge Kim McLane Wardlaw wrote. “We hold only that here, where the executive did not make a discretionary choice to end DACA — but rather acted based on an erroneous view of what the law required — the rescission was arbitrary and capricious under settled law.”

Trump has been ambivalent about the program, except for the view he can end it if he wants.

At times, he has said the program served a useful purpose. That includes saying he considers DACA recipients hard-working and sympathetic, many of them thriving in the only country they have ever known.

“Does anybody really want to throw out good, educated and accomplished young people who have jobs, some serving in the military? Really!” he once tweeted.

He issued a mixed message when the case was argued last fall.

“Many of the people in DACA, no longer very young, are far from ‘angels.’ Some are very tough, hardened criminals,” Trump said in a tweet. But then he added: “If Supreme Court remedies with overturn, a deal will be made with Dems for them to stay!”

The decision was at least the third major case in which the Supreme Court considered the president’s power in regards to immigration.

The justices ended their most recent term in June by stopping the administration’s plan to put a citizenship question on the 2020 Census. Even census experts said such a question was likely to deter noncitizens from returning the forms and impede an accurate population count.

The court ended its 2018 term by approving the president’s travel ban on visitors from a handful of mostly Muslim countries.

The consolidated cases are Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, Trump v. NAACP and McAleenan v. Vidal.

Source: US Government Class

Online Class Discussion – The Judicial Branch

Source: US Government Class

The Judicial Branch

Things that will be covered in this unit.

- The Road to the Supreme Court

- The Appointment and Confirmation of Supreme Court Judges

- Civil Liberties – 1st Amendment

- Supreme Court Cases that deal with Education

The Judicial Branch

The judicial branch of the U.S. government is the system of federal courts and judges that interprets laws made by the legislative branch and enforced by the executive branch. At the top of the judicial branch are the nine justices of the Supreme Court, the highest court in the United States.

What Does the Judicial Branch Do?

From the beginning, it seemed that the judicial branch was destined to take somewhat of a backseat to the other two branches of government.

The Articles of Confederation, the forerunner of the U.S. Constitution that set up the first national government after the Revolutionary War, failed even to mention judicial power or a federal court system.

In Philadelphia in 1787, the members of the Constitutional Convention drafted Article III of the Constitution, which stated that: “[t]he judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”

The framers of the Constitution didn’t elaborate the Supreme Court’s powers in that document, or specify how the judicial branch should be organized—they left all that up to Congress.

Judiciary Act of 1789

With the first bill introduced in the U.S. Senate—which became the Judiciary Act of 1789—the judicial branch began to take shape. The act set up the federal court system and set guidelines for the operation of the U.S. Supreme Court, which at the time had one chief justice and five associate justices.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 also established a federal district court in each state, and in both Kentucky and Maine (which were then parts of other states). In between these two tiers of the judiciary were the U.S. circuit courts, which would serve as the principal trial courts in the federal system.

In its earliest years, the Court held nowhere near the stature it would eventually assume. When the U.S. capital moved to Washington in 1800, the city’s planners failed even to provide the court with its own building, and it met in a room in the basement of the Capitol.

Judicial Review

During the long tenure of the fourth chief justice, John Marshall (appointed in 1801), the Supreme Court assumed what is now considered its most important power and duty, as well as a key part of the system of checks and balances essential to the functioning of the nation’s government.

Judicial review—the process of deciding whether a law is constitutional or not, and declaring the law null and void if it is found to be in conflict with the Constitution—is not mentioned in the Constitution, but was effectively created by the Court itself in the important 1803 case Marbury v. Madison.

In the 1810 case Fletcher v. Peck, the Supreme Court effectively expanded its right of judicial review by striking down a state law as unconstitutional for the first time.

Judicial review established the Supreme Court as the ultimate arbiter of constitutionality in the United States, including federal or state laws, executive orders and lower court rulings.

In another example of the checks and balances system, the U.S. Congress can effectively check judicial review by passing amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Selection of Federal Judges

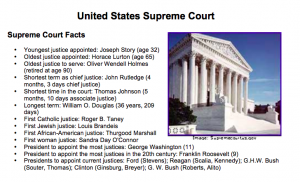

The U.S. president nominates all federal judges—including Supreme Court justices, court of appeals judges and district court judges—and the U.S. Senate confirms them.

Many federal judges are appointed for life, which serves to ensure their independence and immunity from political pressure. Their removal is possible only through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate.

Since 1869, the official number of Supreme Court justices has been set at nine. Thirteen appellate courts, or U.S. Courts of Appeals, sit below the Supreme Court.

Below that, 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has its own court of appeals. The 13th court, known as the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and located in Washington, D.C., hears appeals in patent law cases, and other specialized appeals.

(source: History Channel)

Notes

Handouts

Videos

Source: US Government Class

US Gov Online Class Discussion – 10:45

We will be looking at the Executive Branch

Things you should know about this unit.

- The Many Different Roles of the President

- The Powers of the President

- The Qualifications to Become President

- Role of Vice-President

- Term Limits, Impeachment and the 25th Amendment

Key Questions

- Which of the executive offices do you think is the most important?

- Should the qualification of being a natural born citizen still exist?

- Should the executive office have term limits?

- How hard is it to impeach a president?

- Who have been the most effective presidents?

Source: US Government Class

US Gov Online Class Discussion – May 14th – 10:00

We will be looking at the Executive Branch

Things you should know about this unit.

- The Many Different Roles of the President

- The Powers of the President

- The Qualifications to Become President

- Role of Vice-President

- Term Limits, Impeachment and the 25th Amendment

Key Questions

- Which of the executive offices do you think is the most important?

- Should the qualification of being a natural born citizen still exist?

- Should the executive office have term limits?

- How hard is it to impeach a president?

- Who have been the most effective presidents?

Source: US Government Class

Supreme Court justices warn that Electoral College cases could lead to ‘chaos’

NBC – The Supreme Court on Wednesday wrestled with a dispute over whether Electoral College voters have a constitutional right to diverge from their state’s popular vote in two cases that could have implications for November’s presidential election.

The arguments featured hypotheticals about what would happen if electors were to take a bribe, get hacked by a foreign government or vote for a giraffe.

The justices heard from attorneys for presidential electors in Colorado and Washington state who refused to back Hillary Clinton in 2016 despite her victories in those states. Like most states, Colorado and Washington both require Electoral College voters to vote in line with the state popular vote.

The question in the cases is whether Electoral College voters can be required under state law to vote for the candidate who wins the state popular vote. Lower courts in Colorado and Washington came down on opposite sides of the issue. In January, the top court agreed to weigh in.

A so-called “faithless elector” has never affected the outcome of a U.S. presidential election. Attorneys on both sides, however, have warned that it could happen in a close race.

The justices’ questions largely focused on what limits applied to both electors and states in regulating voting in the Electoral College, America’s system for indirectly selecting presidents.

Larry Lessig, an attorney for the Washington electors, and Jason Harrow, who represented electors in Colorado, argued that states could only remove Electoral College voters for offenses like bribery once they had been convicted.

While the state can require electors to take a pledge to support the candidate who wins the popular vote, they cannot punish an elector who violates that pledge, they argued.

Attorneys for the states argued that electors can be regulated far more strictly. Colorado Attorney General Philip Weiser said that under his view, a state could even bar electors from submitting a vote for a candidate who did not visit the state.

The arguments began at 10 a.m. ET and lasted just under two-and-a-half hours. They were conducted over the phone and streamed live to the public as a precaution against the spreading coronavirus.

The cases came to the high court just months before President Donald Trump will face off against apparent Democratic nominee Joe Biden in November’s contest. Decisions in the cases are expected over the summer.

‘Judges are going to worry about chaos’

Some of the justices warned that siding with the presidential electors could lead to “chaos” in future presidential elections.

Justice Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh both pressed Lessig on the possibility that a win for his clients would unleash chaos.

“Do you deny that that is a good possibility?” Alito asked Lessig.

“I want to follow up on Justice Alito’s line of questioning and what I might call the avoid chaos line of judging,” Kavanaugh said later. Kavanaugh said that when a case is “a close call or tie-breaker,” the top court will generally avoid facilitating uncertainty.

“Just being realistic, judges are going to worry about chaos,” Kavanaugh said.

Lessig responded that he likelihood of chaos was “extremely small.”

“There’s chaos both ways,” Lessig said.

But the justices, including several conservatives, also expressed concerns about giving states too much authority over presidential electors.

“We have to interpret the Constitution to mean what it means regardless of the consequences,” Alito said at one point.

And Kavanaugh asked Weiser why the framers of the Constitution would go through the trouble of establishing an Electoral College if voters in it ultimately lacked discretion.

“What is the purpose of having electors?” he asked.

‘How much difference does it make?’

While much of the questioning focused on the potential chaos that could erupt if enough electors decided to go rogue, some of the justices wondered whether that outcome was all that likely.

“Faithless voting, throughout the years, has always been rare. How much difference does it make?” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked Weiser.

Justice Stephen Breyer told Washington state Solicitor General Noah Purcell that elector discretion “for the most part it hasn’t mattered.”

“Where it really might matter is if somebody died or if some catastrophe happened or worse,” Breyer said.

Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested that the court might have erred by taking the case at all.

Source: US Government Class

AP Gov Online Class Discussion – May 13th

Source: US Government Class

Executive Branch

Things you should know about this unit.

- The Many Different Roles of the President

- The Powers of the President

- The Qualifications to Become President

- Role of Vice-President

- Term Limits, Impeachment and the 25th Amendment

The Many Different Roles of the President

The power of the Executive Branch is vested in the President of the United States, who also acts as head of state and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The President is responsible for implementing and enforcing the laws written by Congress and, to that end, appoints the heads of the federal agencies, including the Cabinet. The Vice President is also part of the Executive Branch, ready to assume the Presidency should the need arise.

The Cabinet and independent federal agencies are responsible for the day-to-day enforcement and administration of federal laws. These departments and agencies have missions and responsibilities as widely divergent as those of the Department of Defense and the Environmental Protection Agency, the Social Security Administration and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Including members of the armed forces, the Executive Branch employs more than 4 million Americans.

The President

The President is both the head of state and head of government of the United States of America, and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

Under Article II of the Constitution, the President is responsible for the execution and enforcement of the laws created by Congress. Fifteen executive departments — each led by an appointed member of the President’s Cabinet. They are joined in this by other executive agencies such as the CIA and Environmental Protection Agency, the heads of which are not part of the Cabinet, but who are under the full authority of the President.

The President has the power either to sign legislation into law or to veto bills enacted by Congress, although Congress may override a veto with a two-thirds vote of both houses. The Executive Branch conducts diplomacy with other nations, and the President has the power to negotiate and sign treaties, which also must be ratified by two-thirds of the Senate. The President can issue executive orders, which direct executive officers or clarify and further existing laws. The President also has unlimited power to extend pardons and clemencies for federal crimes, except in cases of impeachment.

The Qualifications to Become President

The Constitution lists only three qualifications for the Presidency — the President must be:

- 35 years of age

- be a natural born citizen, and

- must have lived in the United States for at least 14 years.

The Vice President

The primary responsibility of the Vice President of the United States is to be ready at a moment’s notice to assume the Presidency if the President is unable to perform his duties. This can be because of the President’s death, resignation, or temporary incapacitation, or if the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet judge that the President is no longer able to discharge the duties of the presidency.

The Vice President is elected along with the President by the Electoral College — each elector casts one vote for President and another for Vice President. Before the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804, electors only voted for President, and the person who received the second greatest number of votes became Vice President.

The Vice President also serves as the President of the United States Senate, where he or she casts the deciding vote in the case of a tie. Except in the case of tiebreaking votes, the Vice President rarely actually presides over the Senate. Instead, the Senate selects one of their own members, usually junior members of the majority party, to preside over the Senate each day.

Executive Office of the President

Every day, the President of the United States is faced with scores of decisions, each with important consequences for America’s future. To provide the President with the support that he or she needs to govern effectively, the Executive Office of the President (EOP) was created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EOP has responsibility for tasks ranging from communicating the President’s message to the American people to promoting our trade interests abroad.

The Cabinet

The Cabinet is an advisory body made up of the heads of the 15 executive departments. Appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, the members of the Cabinet are often the President’s closest confidants. In addition to running major federal agencies, they play an important role in the Presidential line of succession — after the Vice President, Speaker of the House, and Senate President pro tempore, the line of succession continues with the Cabinet offices in the order in which the departments were created. All the members of the Cabinet take the title Secretary, excepting the head of the Justice Department, who is styled Attorney General.

Source: whitehouse.gov

Handout

Videos

Source: US Government Class

US Gov Online Class Discussion – May 7th – 10:45

Source: US Government Class