The Judicial Branch

Things that will be covered in this unit.

- The Road to the Supreme Court

- The Appointment and Confirmation of Supreme Court Judges

- Civil Liberties – 1st Amendment

- Supreme Court Cases that deal with Education

The Judicial Branch

The judicial branch of the U.S. government is the system of federal courts and judges that interprets laws made by the legislative branch and enforced by the executive branch. At the top of the judicial branch are the nine justices of the Supreme Court, the highest court in the United States.

What Does the Judicial Branch Do?

From the beginning, it seemed that the judicial branch was destined to take somewhat of a backseat to the other two branches of government.

The Articles of Confederation, the forerunner of the U.S. Constitution that set up the first national government after the Revolutionary War, failed even to mention judicial power or a federal court system.

In Philadelphia in 1787, the members of the Constitutional Convention drafted Article III of the Constitution, which stated that: “[t]he judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”

The framers of the Constitution didn’t elaborate the Supreme Court’s powers in that document, or specify how the judicial branch should be organized—they left all that up to Congress.

Judiciary Act of 1789

With the first bill introduced in the U.S. Senate—which became the Judiciary Act of 1789—the judicial branch began to take shape. The act set up the federal court system and set guidelines for the operation of the U.S. Supreme Court, which at the time had one chief justice and five associate justices.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 also established a federal district court in each state, and in both Kentucky and Maine (which were then parts of other states). In between these two tiers of the judiciary were the U.S. circuit courts, which would serve as the principal trial courts in the federal system.

In its earliest years, the Court held nowhere near the stature it would eventually assume. When the U.S. capital moved to Washington in 1800, the city’s planners failed even to provide the court with its own building, and it met in a room in the basement of the Capitol.

Judicial Review

During the long tenure of the fourth chief justice, John Marshall (appointed in 1801), the Supreme Court assumed what is now considered its most important power and duty, as well as a key part of the system of checks and balances essential to the functioning of the nation’s government.

Judicial review—the process of deciding whether a law is constitutional or not, and declaring the law null and void if it is found to be in conflict with the Constitution—is not mentioned in the Constitution, but was effectively created by the Court itself in the important 1803 case Marbury v. Madison.

In the 1810 case Fletcher v. Peck, the Supreme Court effectively expanded its right of judicial review by striking down a state law as unconstitutional for the first time.

Judicial review established the Supreme Court as the ultimate arbiter of constitutionality in the United States, including federal or state laws, executive orders and lower court rulings.

In another example of the checks and balances system, the U.S. Congress can effectively check judicial review by passing amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

Selection of Federal Judges

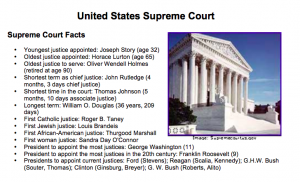

The U.S. president nominates all federal judges—including Supreme Court justices, court of appeals judges and district court judges—and the U.S. Senate confirms them.

Many federal judges are appointed for life, which serves to ensure their independence and immunity from political pressure. Their removal is possible only through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate.

Since 1869, the official number of Supreme Court justices has been set at nine. Thirteen appellate courts, or U.S. Courts of Appeals, sit below the Supreme Court.

Below that, 94 federal judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of which has its own court of appeals. The 13th court, known as the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and located in Washington, D.C., hears appeals in patent law cases, and other specialized appeals.

(source: History Channel)

Notes

Handouts

Videos

Source: US Government Class